Vietnam fetes U.S., Aussie plastic surgeons on 50th anniversary of center

At the height of the Vietnam war in 1969, New York plastic surgeon Arthur Barsky Jr., MD, and attorney Thomas Miller organized a medical-relief effort to treat South Vietnamese children who sustained injuries as a result of the fighting in the region. Their efforts quickly extended to children who had sustained trauma unrelated to war and who suffered from disease-driven or congenital abnormalities – whether they were from North or South Vietnam.

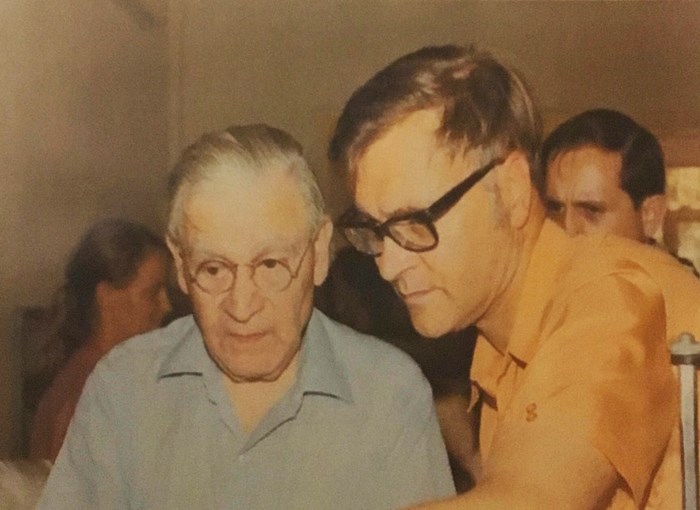

The pair overcame logistical and bureaucratic obstacles to establish Children's Medical Relief International (CMRI) in Saigon – now Ho Chi Minh City – which was soon followed by construction of the CMRI Plastic and Reconstructive Surgical Center, the first permanent structure dedicated to the reconstructive surgical care for the Vietnamese people, and the only modern plastic surgical unit in Vietnam. Dr. Barsky and Miller recruited a medical team of international volunteers – and the surgical center became unofficially known as the Barsky Unit.

A half century after its founding, ASPS member William McClure, MD, Napa, Calif., traveled to Ho Chi Minh City to take part in an anniversary celebration held March 27- 29 in honor of the Barsky Unit. Dr. McClure, who began performing volunteer medical work in 1989 in Vietnam, had been intrigued that the Vietnamese government held the Barsky Unit volunteers in such high esteem. Although Dr. McClure was too young to have been involved in its original incarnation, he says he was inspired during his plastic surgery residency by 1983 ASPS President Mark Gorney, MD, and Robert Mills, MD, both Stanford (Calif.) University professors, who took time away from their personal and professional lives to serve with the Barsky Unit in the early 1970s. (Dr. Mills, in fact, gave up his practice and moved to Saigon in 1973 in order to stay in the country and work permanently in the unit.)

Historic links

The late Dr. Gorney, who led a multitude of humanitarian missions around the globe during his career, first traveled to Vietnam in the late 1960s to provide care with the Barsky Unit – he was the reconstructive surgeon who treated Phan Thi Kim Phuc, the young Vietnamese village girl whose photograph taken immediately after having been burned by napalm dropped by South Vietnamese military planes shocked the world.

Dr. Barsky, too, had experience treating patients wounded in war: He had arranged for "The Hiroshima Maidens," as they were dubbed – 25 Japanese women injured by the first atomic bomb dropped on Japan in 1945 – to travel to New York in 1955, where they lived with American families while undergoing reconstructive surgery and other treatment.

Lester Silver, MD, New York, was Dr. Barsky's resident and flew to Saigon not long after Dr. Barsky established the unit. As the unit's professional services director, he performed surgeries, lectured, taught local surgeons reconstructive techniques and "made sure the physicians who were coming into the country were able to execute some continuity of care," he says. "Then I'd go back twice a year to recheck and see if anything needed to be changed or updated."

One such trip came on the eve of the fall of Saigon. "Dr. Barsky wanted me to see if I could help get some of our people out – which we did, in fair number," Dr. Silver recalls. "I left the day before Saigon fell."

Although Dr. Silver was unable to return to Vietnam for the celebration in March, he shared memories with PSN of the work, which often involved flights from Saigon into the countryside to gather injured children and return them to the unit, which could be a dangerous undertaking.

"In the early days, in the middle of the war, there was a little more to be gained or lost," he says. "However, the military was there, so we were more or less protected.

"The plastic surgeons who served with Dr. Barsky weren't really concerned for our safety," Dr. Silver adds. "If you were concerned, you didn't go there. But life is funny; once you realize that the worst thing that can happen is that you could die, you don't worry about that."

The Barsky Unit's early efforts were aided by several Australian physicians who signed-on after hearing of the efforts underway in Saigon. Australian surgeon Rowan Story, MD, who first traveled to Ho Chi Minh City for medical work in 1998, had heard his colleagues speak of the fabled Barsky Unit and began researching it to quell his curiosity, which brought him in contact with Dr. McClure.

The current now unified Vietnamese government surprised Dr. Story by inviting him to help plan the 50th anniversary ceremony at the original site of the former Barsky Unit clinic at the Ministry of Health's National Hospital of Odonto-Stomology in Ho Chi Minh City.

Dr. McClure says the idea of being invited to partake in celebrations by a government that had once been considered an enemy was an honor.

"I brought my wife, sister and two of my four children, and Dr. Gorney's widow, Gerry, had been invited and accompanied us. Many Australians attended, including family members of previous volunteers who had passed away," he tells PSN. "Vietnamese nurses and administrators who staffed the unit 50 years ago also attended – they were reunited with Western counterparts who they hadn't seen in 50 years. That was very heartwarming."

The ceremony was attended by nearly 300 people.

"Many very nice speeches were given and our hosts played a video-documentary they'd assembled to honor the international members," Dr. McClure says. "In addition, the hosts had gathered old photographs of the Barsky Unit and its personnel, and made them into giant posters. It was cute seeing these Vietnamese former nurses, now little old ladies, standing in front of the posters and pointing at themselves as they looked when they were in their 20s."

One Barsky Unit nurse in particular was praised for her quick thinking, Dr. McClure notes. "Just before Saigon fell in 1975, the head nurse grabbed all the instruments and hid them at her home in Vietnam, to save them from looting. When the clinic reopened in the early 1990s, she brought all of them back. She became a hero – because the Vietnamese had an acute shortage of equipment."

'Wonderful experience'

Perhaps the most impressive development of all, he says, was the attention and respect bestowed upon the unit's former volunteers and family members by young Vietnamese medical professionals, now two generations removed from the war.

"They were fascinated by the pictures and the video – it was very touching," Dr. McClure says. "And for Mrs. Gorney, meeting the Vietnamese medical professionals who had worked with Mark and had admired him was particularly moving. It was a wonderful experience.

"It was a surprise to us that the Vietnamese government wanted to celebrate this anniversary," he adds. "This is a communist government, which had once been our 'enemy,' and they wanted to honor the international volunteers who came to Vietnam from countries at war against them. We were blown away."

Although opposing governments were at war, non-political medical professionals recognized that children on both sides of that Southeast Asian border desperately needed medical help – and they assembled the physicians from the West who were able and willing to make the sacrifices necessary to serve those children.

"Everyone realized that the entire effort of the Barsky Unit volunteers and all that followed was undertaken solely for the children – they were the innocent victims of the war," Dr. McClure says. "Politics never entered into it. And even though Americans and Australian troops had been fighting against them, the Vietnamese realized that these physicians and nurses gave up a lot in their personal lives to go halfway across the world to do this. That was a large part of rationale behind this celebration."