Targeted muscle reinnervation to end amputation nerve pain

Editor's note: The following is part of an ongoing series highlighting The PSF Research Grant Award winners, and research they're conducting to improve patient safety and develop new technologies for plastic surgeons. These features examine research funding awarded prior to the current year, as projects to which grants were awarded this year may not yet have results ready to discuss.

THE RESEARCHER

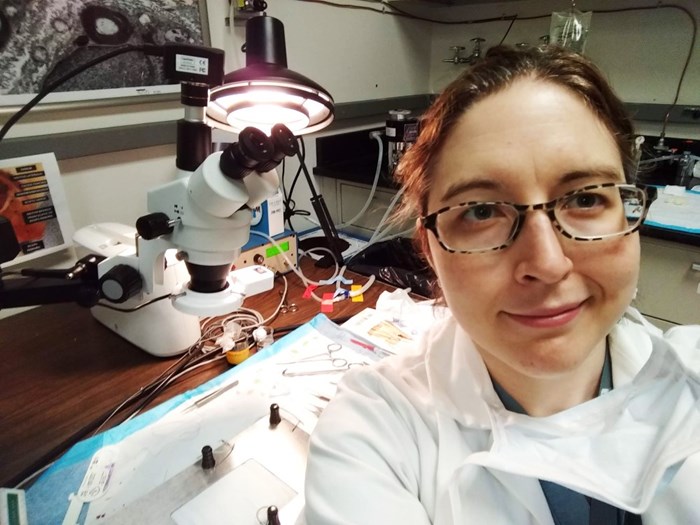

Gwendolyn Hoben, MD, PhD

Title: Assistant Professor of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

Award: AAHS/ PSF Combined Pilot Research Grant

Project: Targeted Muscle Reinnervation in a Neuropathic Pain Model

PSN: Can you tell us what you're working toward with this project?

Dr. Hoben: Targeted muscle reinnervation (TMR) has been an exciting addition to plastic surgery's armamentarium – and the clinical outcomes, particularly for amputation-related pain, are changing the face of amputation care. TMR is a procedure in which nerves that have been cut during an amputation are redirected to remaining small muscular branches, in order to improve control of upper-limb prosthetics and relieve pain. My work focuses on examining the mechanisms and changes taking place at the neuronal and axonal levels following TMR, with an emphasis on how they affect pain-related outcomes.

Surgical treatments for nerve-related pain, such as TMR or neuroma excision, manipulate pain pathways in a different way compared to medical interventions, which makes them particularly interesting to study. Understanding how the coaptation of mixed sensory-motor nerves to small motor-branches changes axonal regeneration and affects neuronal activity may give insight into other ways we can treat pain and manipulate regeneration.

PSN: How far along are you in your research?

Dr. Hoben: The first step in moving forward with these studies has been developing an animal model with a pain phenotype that can be measured repeatedly over time. Happily, this model has shown that TMR clearly reduces rodent pain behaviors. Currently, we're looking at changes in spontaneous behaviors that may give insight into anxiety and depression. It's been interesting to parse-out how TMR versus neuroma excision alone appears to differently affect allodynia, hyperalgesia and cold sensitivity.

PSN: Are there any particular conditions that you would you like to change as a result of this nerve-related research?

Dr. Hoben: One of the big questions in TMR is how efficacious it can be for chronic amputations. At the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) – as in other centers – we're working hard to perform TMR on the acute amputees that we see, but the much larger population of chronic amputees with chronic pain is a bigger challenge. It's possible there are modifications in TMR or adjunctive therapies that may improve efficacy in chronic amputees, and I'm hopeful that studying these mechanisms through the support of The PSF research grant may give insight into treating chronic, neuropathic pain conditions.

PSN: Has anything unexpected surfaced that might change the focus of the research?

Dr. Hoben: The link between reinnervation and spontaneous afferent activity associated with pain is well-established; this made us suspect that ongoing pain after simply excising the neuroma would be extinguished once that sciatic nerve had regenerated. However, studying this in a rat model is challenging because, unlike humans, they can regenerate a 3-cm. segment of the sciatic nerve with ease. We have been surprised, though, to see that even with reinnervation, some pain behaviors appear to persist and may reflect more permanent neuronal changes.

PSN: What's been your approach to divining what may be behind this?

Dr. Hoben: A lot of hypotheses, and a lot of work to do!

PSN: Who are your mentors and key collaborators on this project?

Dr. Hoben: I've been fortunate to find some amazing collaborators at MCW in the field of pain: Cheryl Stucky, PhD, and Quinn Hogan, MD. Cheryl's group has played a key role in describing some of the critical receptors in pain and has made fascinating discoveries about the role of keratinocytes in pain sensation with a model of surgical incisions. Her work has certainly made me think more deeply about the incisions I make in the O.R. Quinn's group has made critical discoveries in dorsal-root ganglia stimulation for neuropathic pain and glial-cell regulation in peripheral nerve injury. They are powerhouses in the field of pain – and I have learned a tremendous amount from their work and in collaboration with them. Despite making it through residency and graduate school, I still have a great deal to learn about pain!

I'm also thankful for the mentorship of all my brilliant partners at MCW, some of whom are already legends in plastic surgery research, and my mentors from residency at Washington University in St. Louis, without whom I would not have this research love affair with nerves.

PSN: What did you want to be when you grew up?

Dr. Hoben: Per my parents, at varying times I planned to become a fighter pilot, professional hockey player and/or the president. For better or worse, those didn't work out. Some things they all have in common are strategy, perseverance – and some risk. In my role as a clinician scientist, formulating questions and designing experiments to answer them is a form of strategy – and keeping a lab afloat is certainly an example of perseverance and embracing reasonable risk with new ideas.

PSN: Aside from this work, what has been your favorite research project to date?

Dr. Hoben: I like to joke that no cow should have to suffer from knee meniscus arthritis. My thesis work examined cell sources and tissue organization to create a knee meniscus. We commonly used bovine chondrocytes, because one cow meniscus could provide a lot of cells and we had a pretty good deal with a local abattoir to provide cow knees. Given enough time and cells, I can make a functional cow meniscus. Sadly, cow knees are not known for being tasty – otherwise my butchery skills would have a practical application.

PSN: How do you spend your time away from the lab?

Dr. Hoben: I try to spend as much time as possible with my husband and son. In particular, I love doing crafts and building things with my son. We recently completed a lamp made from repurposed circuit boards. I've recently begun introducing him to power tools – we're having a lot of fun.

PSN: What kind of music do you like to listen to in your lab?

Dr. Hoben: My favorite playlist has everything from EDM to classic country – a little something for everyone. Some of the more eclectic selections are tracks from the O.R. playlists of my mentors, and when those tracks play, it reminds me of them

For more information about the many research studies funded by The PSF or to support our current and future research initiatives, please go to ThePSF.org.