Consult Corner: Orbital floor fracture

Message on your pager: 23 YOM S/P ASSAULT W/ ORBITAL FLOOR FX. C/F ENTRAPMENT. You're sewing a face laceration in the E.D. when your pager goes off. Discussion with the E.D. provider concerns an intoxicated, 23-year-old male who was involved in a bar fight. CT of the face confirms the presence of a unilateral orbital floor fracture. The provider is keen to point out that the radiologist is concerned for ocular entrapment and asks you to urgently evaluate.

Description of the condition

The orbit is composed of seven different bones, the structure of which generally serves as a shock absorber for the globe. The thin-walled orbital floor is composed of mainly the maxillary bone and is the most fractured segment. The optic foramen is located approximately 40-45mm posterior to the inferior orbital rim and is superior to the horizontal plane of the orbital floor. Orbital floor fractures may occur in isolation or as part of a pattern, such as zygomaticomaxillary complex and naso-orbital-ethmoid fractures. The incidence of globe injury with orbital fractures ranges from 14-30 percent and may present as a corneal abrasion, retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, traumatic hyphema or globe rupture. Less than 5 percent of fractures may result in the formation of a retrobulbar hematoma, which, in the presence of orbital compartment syndrome, requires emergent attention. While uncommon, fractures of the orbit may extend posteriorly and involve CN III, IV, V1 and VI, resulting in superior orbital fissure, or Rochen-Duvigneaud syndrome. When the optic nerve is also involved, the diagnosis becomes orbital apex syndrome. Fortunately, the overall incidence of vision loss with orbital

fractures is below 2 percent.

Initial evaluation

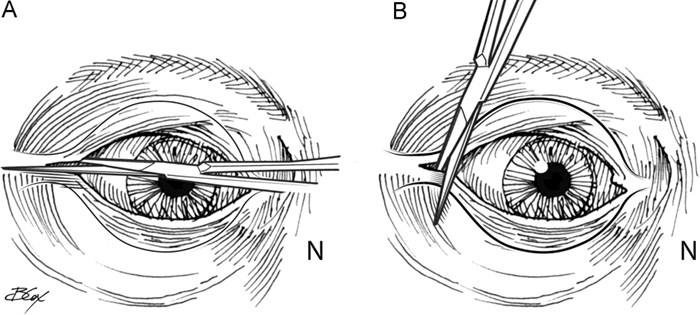

It's important to remember that patients with orbital floor fractures are also trauma patients. Emphasis should be placed on evaluating for concomitant traumatic brain or cervical spine injuries. In addition to a comprehensive facial exam, it's paramount to check pupil reactivity and visual acuity. Red desaturation may be an early finding in patients with traumatic optic neuritis. With the eyes open and in neutral position, the examiner may evaluate for enophthalmos, exophthalmos and telecanthus. Extraocular movements are tested with particular emphasis on vertical gaze as the inferior rectus is the most common muscle to become entrapped in the orbital floor. In a patient who is unable to cooperate with examination, a forced duction test with topical anesthetic may be used to evaluate for entrapment. In the setting of a fracture, ocular movements can be limited for multiple reasons, and the clinical diagnosis of ocular entrapment is only made when a patient has extreme difficulty moving the eye in a direction that correlates with fracture anatomy. Ocular movements in this setting are often accompanied by severe pain, nausea and/or vomiting.

A rare complication of posterior orbital floor fractures and retrobulbar hematomas is stimulation of the oculocardiac reflex. This may result in bradycardic dysrhythmias causing hemodynamic derangement, nausea, vomiting and/or vertigo. This is a surgical emergency mandating immediate open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). In the setting of elevated intraocular pressure (normal 10-21mmHg), lateral canthotomy and inferior cantholysis should be performed at the bedside. In general, there should be a low threshold for consulting Ophthalmology in patients with orbital floor fractures – especially patients with traumatic optic neuritis and those felt to be operative. A thorough post-traumatic ocular exam is critical before embarking on procedures that may further traumatize the globe.

Radiographically, the fracture may be characterized by measuring its size in the coronal and sagittal views. This also provides the opportunity to delineate associated fractures. Blood is almost always identified within the ipsilateral maxillary sinus, and herniated orbital fat may also be found here. "Rounding" of the inferior rectus and herniation of orbital contents into the adjacent sinuses are common imaging findings and may predict enophthalmos, but they aren't predictors of orbital entrapment.

Management

Orbital floor fractures may be managed non-operatively if they are small and do not result in functional impairment of the eye. Acute indications (within 24 hours) for repair are ocular entrapment; the presence of the oculocardiac reflex; superior orbital fissure or orbital apex syndromes; or ocular hypertension caused by decreased orbital volume refractory to medical management. Additional non-urgent indications include large fracture (>2cm or >50 percent of floor volume) or clinically significant enophthalmos (>2mm). Relative contraindications generally encompass acute injuries to the globe, requiring ophthalmologic intervention, medical instability and contralateral blindness.

Surgical approach

The goals of surgery are the restoration of orbital support and normalization of orbital volume. Under general anesthesia and following a thorough eye exam with baseline forced ductions, the fracture is exposed through one of several approaches. Herniated contents are gently reduced, and the orbital process of the palatine bone (the posterior "ledge") is identified. Reconstruction of the orbital floor is most-often performed with a synthetic implant, but bone graft or alternative alloplastic material may be used in the setting of heavy contamination or in the pediatric population to accommodate future growth. Prior to closure, the eyes are examined for proper globe position and a forced duction test is performed once again. Many surgeons will place a lid suspension suture to prevent the development of lower-lid ectropion. Patients are admitted postoperatively and given perioperative antibiotics at the surgeon's discretion. Serial visual examinations are conducted to ensure freedom of the extraocular muscles.

Case conclusion

The 23-year-old patient was found to have a 2.5cm x 1.4cm pure orbital floor blowout fracture and no other traumatic injuries. His visual acuity was preserved and he did not have clinical evidence of entrapment or a globe injury. Once sober, he was discharged from the E.D. and underwent ORIF later that week. He was observed for a night in the hospital and discharged the next day.

Dr. Criman is PGY-6 in the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Department of Plastic Surgery.